by Jason Farrell

A rubbery body. A determined look, one bulging eye noticeably larger than the other. A dashing, daring hero with a robotic suit and a ray-gun who also happens to be the most innocuous and least daring of all creatures: a worm. This was Earthworm Jim, a 1994 Super Nintendo video game, and my first exposure to the wacky, and yet remarkably consistent, mind of Doug TenNapel.

I still love video games, but comics are my first and greatest love. Turns out that also seems to be true for Doug TenNapel as well. He's had a long and successful career in gaming and animation (among other pursuits), but some of his most prolific output has been in the realm of graphic novels where he puts out about one full length graphic novel per year. I've been reading them nearly that long, and he's still mining the territory where the ridiculous and the ordinary meet as effectively as he ever had. Even when there are more brightly colored books jockeying for attention on the shelves of bookstores and comics shops, his work still stands out.

Here's a punchline you probably didn't expect: Supposedly, I should hate Doug TenNapel's work. Or at the very least, i should avoid it like the plague.

There are a few things that TenNapel is known for. His art style is instantly recognizable: thick lined, gangly, exaggerated figures, with jaws that drop several inches further than looks comfortable, and limbs that stretch and bend in near impossible ways. He writes about family, fathers and sons in particular, and how those bonds endure even the most spectacular trials. He loves to create and draw bizarre creatures, often the result of ordinary, harmless creatures being mashed together or mutated in newly deadly ways. And, as has been heavily reported by many who discuss his work, there is often a significant spiritual component to his stories. Doug TenNapel himself is a practicing Christian, and themes of morality, conversion and faith pervade his stories.

I'm not a Christian. I'm not a religious person at all. I'm an atheist, and while I try not to discriminate against any belief system that is not actively antagonistic to life or free thinking, I am fairly sensitive to dogma, and to proselytizing of all kinds. I'm not interested in fiction that tells me how to feel, how to act, or how to live my life. Tell me about your characters, authors, and their lives, and let me draw my own conclusions. If it's heavy handed, if it sacrifices plausibility and narrative momentum and the humanity of characters in favor of serving an ideological agenda, it's no longer fiction. At the very least, it's no longer fiction I have any time for.

It had been fully ten years since I'd read my first TenNapel book which was Creature Tech, which i then re-read in preparation for this article. I remembered it as a funny, slightly mad romp, with the kind of imaginative blend of weird technology and mutated creatures that populate most of his work, along with strained familial relationships, hope, and a generous dollop of bathroom humor and silly puns. Somehow, I didn't remember religion or faith playing a major role in the story's themes.

And yet, there it was, everywhere. It wasn't subtle: at one point late in the story, our protagonist Dr. Michael Ong is transported by a symbiotic creature that has grafted itself to his chest (replacing his heart in the process) to a mysterious alternate dimension. There, a similar creature is stretched out on a frame, its four limbs nailed to the corners like Jesus on the cross. As he gazes up at the creature, a previously agnostic Michael is converted before our eyes. He's returned to Earth, his chest completely healed, and when his religious father remarks on his transformation with surprise, Michael simply says, “I got saved, Pop!”

There are other religious elements as well. The macguffin that is sought by the evil space eel riding villain of the story, Dr. Jameson, as well as by our heroes, is the Shroud of Turin, the burial shroud of Jesus Christ, an artifact thought to be capable of healing injuries and illnesses up to and including death itself, a legend proven true as the story progresses. So, how is it possible that I missed this? That I could be that inattentive a reader beggars belief.

And indeed, it's not that I missed the spiritual elements of this story (or in any of Doug TenNapel's work) as to some degree or another they are present in them all. What I found is that it didn't matter. The humanity and humor with which TenNapel approaches his subjects, and the principles that he stands for behind whatever trappings, religious or otherwise, they're dressed in, are principles that I wholeheartedly believe in: family, individuality, thinking for oneself, multiple belief systems co-existing in harmony.

Frequently, TenNapel shows the flexibility in his worldview for both many different views of religion, as well as differing methods for achieving our (limited) understanding of the universe (empirical, spiritual, etc.) There is a lack of judgment about which is superior or “right,” provided that the belief system in question allows its adherents to maintain their individuality. It's only when a belief system threatens to overwhelm its members with a 'Invasion of the Body Snatchers' like group-think that the author's own disapproval is evident.

In Creature Tech, Michael Ong is a scientist, as is his primary assistant, Jim. Jim is a long way from Levi, the kooky proprietor of a museum of the weird, who thinks that a dried up cinnamon roll has the face of Jesus. He is, as Dr. Ong calls him, “one of the smartest guys I've ever met.” When Jim attributes his intelligence to being “god-given”, Michael accuses him of using God as a crutch, and reminds him that many of the world's stupidest people believe in God. He also tells him that “a good scientist doesn't mix his personal beliefs with research.” Jim response to that is repeated, in some form or indirectly, again and again throughout TenNapel's work. “That's not science by definition,” Jim tells him, “It's stupid to research a problem then arbitrarily restrict the options available to solve that problem.”

Later, Michael has an argument with his father over a similar subject, and tells him essentially that he isn't smart or educated enough to debate with Michael on the subject of science. When told bluntly by his son to choose God or reason, his father tells him that he chose God because of reason. The message, again, is not that theology is superior to science, but rather that one shouldn't supercede the other; the acceptance of God is not a tacit rejection of logic and reason, or vice-versa.

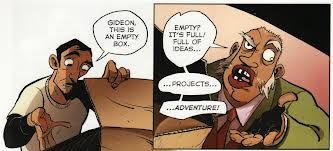

In Cardboard, TenNapel's most recent published work, a Mr. Wing-like old man named Gideon sells a down on his luck contractor a cardboard box which turns out to have...unusual properties, shall we say.

Whatever the cardboard is used to make becomes fully sentient (if the creation would normally be sentient in its flesh and blood incarnation). After complications with the cardboard ensue, Mike confronts Gideon, demanding answers. An increasingly bemused Mike is told, in turn, that the cardboard was made by an alien species, who were also wizards, who were also particle physicists, who were also religious. Exasperated by these slippery definitions, Mike storms off in a confused huff. Once again TenNapel demonstrates his idea that many different ideologies can share a harmonious co-existence, even if our stubborn brains are often unwilling to easily accept it.

Similarly, TenNapel's idea of humanity isn't limited to biological humans, and their spiritual life isn't limited to a Christian idea of heaven (with chubby, harp playing cherubs and puffy, white clouds). They're in there: near the end of the western Iron West, the sheriff dies defending his town, and we see him next sitting on just such a cloud (although angels, chubby or otherwise, are not in evidence.) True to TenNapel's inclusionary ideals, however, there are several other beliefs systems and afterlives in evidence throughout his work. In the same work, a shaman calls upon “The Great Spirit” to heal protagonist Preston Struck, news Struck receives with equanimity.

In Creature Tech, a two legged mantis creature dubbed “Blue” by the locals suffers a seemingly fatal wound before being revived. In the meantime, we're given a glimpse of the insect heaven he ends up in, a place that looks very much like Olympus with more antennae. In the methods of his recovery, we see more evidence of TenNapel's egalitarian approach, as well as his lack of force feeding us answers: Michael Ong uses science to try to save him, while his father appeals to a higher power. When Blue rises, gasping, back to consciousness, we're left to decide on our own which method proved effective. It would probably be most in the spirit of his work to decide it was a bit of both.

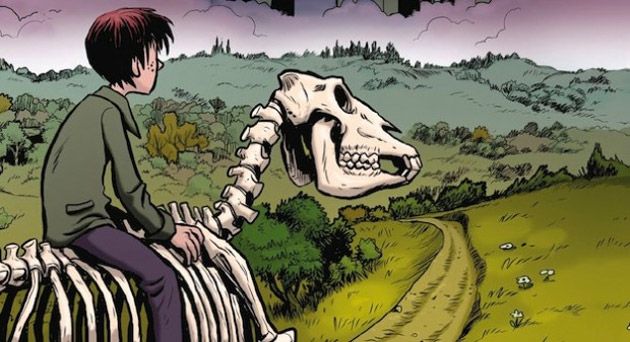

In Ghostopolis, the title dimension is a kind of purgatory that lies between our world and a more traditional Christian heaven, which is only hinted at. Although ruled by evil mummies, goblins and their overlord Vaugner when our story opens, it is not, by definition, a place for the wicked. Claire, a ghost, not only exists in TenNapel's cosmology, but ends up being voted to be the new "Lord of the Afterlife", taking over for the defeated Vaugner. And she does so with Frank Gallows, one of the primary protagonists of the story, at her side. This world of skeletal horses and werewolves is not just a way point for the seeker on his or her way to that land of clouds and cherubs, but a worthy destination in its own right.

All of these different creatures, and many more, possess their own nobility and purpose in TenNapel's broad universe. The heart and faith of a confused boxer made of cardboard is no less valid than that of a human preacher. His characters are very often unsure, even wounded, but as long as they are grasping toward understanding, they have his sympathies. The search for truth is not a competition with winners and losers, but rather a pursuit that all thinking beings must undertake. This is a journey that has, for TenNapel, as many different approaches as there are thinking beings. As I mentioned before, it is only those who threaten to stifle this curiosity, this search for truth, who are overtly “wrong” in his stories. The mechanical army in Iron West, machines that consider humanity “stupid, lazy and inefficient.” The worker drone-like creatures in Cardboard, who seek to plaster their favorite material over everything, smothering it. The bugs in Earthboy Jacobus, who are so alarmed by Jacobus' ability to withstand their brainwashing that they dedicate decades to tracking down a single boy. These are the enemies in Doug TenNapel's fiction, that is a message I can get behind.

Despite the strength of TenNapel's characterizations, his amazing, fluid, vibrant drawing, the diversity of his settings, the imagination brimming from every page, his humor, and his heart, I wouldn't have been able to overlook a core message of “this is wrong and this is right; this is the proper way to live.” That's a message of exclusion, of narrow mindedness, and it couldn't be further from what TenNapel stands for, as evidenced again and again in his considerable body of work, a world big enough to include whale airships, pet Tyrannosaurs, islands made from interstellar princes and, thankfully, every one of us.

Beautiful article: Smoothly written and true to its subject. Makes me want to read more TenNapel.

ReplyDeleteWonderfully put sir! After making it a goal this year(and reaching it!) of having all 13 of TenNapel's graphic novel's I can never get enough of his work. I'm excited to read them to my newborn when he gets old enough(aside from maybe Black Cherry, at least til he gets into high school :D). I mean I know he has a moral story sewn into the books, but it's what makes them so good!

ReplyDeleteNEXT UP! His Kickstarter! http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1812253609/doug-tennapel-sketchbook-archives

Thanks for reading, guys, and for the kind words.

ReplyDeletewell written, boss...what else have you published??

DeleteNot a whole lot, Mike, but thanks for asking. Hopefully that will change soon. For now, there's another (Vertigo related) piece on The Chemical Box, and around eight short pieces over here: http://comixnonsense.blogspot.com/

Delete